From Eritrea to Sudan to Iraq to Egypt to America: Samira’s Perspective on War

by Thomas B., May, 2013

I interviewed an Eritrean woman named Samira. Samira had to flee Eritrea because of war. The experience of being forced to leave Eritrea and subsequent experiences affect Samira’s perspective on war. After exile from Eritrea, being a refugee in Sudan, and briefly living in Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war, Samira was “sick and tired of war.” Samira is skeptical of armed struggles and the insistence of authorities that they are necessary. Eritrea was plunged into thirty years of strife, and in fact it is still facing the threat of conflict. She is disappointed in the government that her country got when it gained independence. From her statements in our conversation, I believe Samira sees violence, even violence done in the name of a cause that appears just, as a never-ending cycle.

Eritrea is a country of six point two million people on the Eastern coast of Africa (Eritrea). To the East lies the Red Sea. Across the sea one will find Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The Southern half of Eritrea is a relatively thin region of land that hugs the coast. In the West the country fans out to cover more inland areas. Eritrea has been subject to continuous strife as a victim of imperialism, regional rivals and an oppressive government. It is a poor country, where one million people face starvation (Masci) and the per capita income is just $680.

The roots of Eritrea’s Independence War go back almost 125 years, to 1890, when Eritrea became an Italian colony. Eritrea remained under Italian domination until Italy ended up on the losing side of the Second World War. In 1949 Eritrea became a United Nations trust territory administered by Britain. In the early 50s, the United Nations made the deadly mistake of turning control of Eritrea over to its larger neighbor to the South West, Ethiopia. This mistake led to decades of strife for Eritrea and Ethiopia.

That the roots of the conflict go back into history many generations is connected to Samira’s perspective that violence is a cycle that feeds on itself, not a confrontation between good and evil that resolves itself. She said of the current problems in Eritrea that “the cycle, the violence just continues.” The cycle of violence that began with Italy colonizing Africa has continued to the present day.

Eritreans waged a long struggle against Ethiopia for independence with Ethiopian forces who fought to hold on to the territory. From 1974 to 1987, Ethiopia was ruled by a Marxist-Leninist government called the Derg. The Soviet Union and Cuba became involved in the fighting, in support of the Derg. Eritrean guerillas persisted in the face of superior military technology and numbers, and for thirty years the Independence War brought strife to the region. The war took a heavy toll on Eritrea, Ethiopia, and neighbors. A famine in Ethiopia and Eritrea in 1984-85 killed approximately one million people (Masci). Many fled to find safety elsewhere. In 1991 Eritrean independence fighters won a military victory against Ethiopia that led to a 1993 referendum in which the Eritrean people voted for independence from Ethiopia.

Samira and other Eritreans hoped that the Independence War would lead to a democratic, accountable government for Eritrea. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. In Samira’s words, “…right now, the people who were fighting to liberate [Eritrea], supposedly, are the one’s who are torturing the people. Right now, my story might be like nothing compared to the thousands and thousands fleeing the country.” As so often happens in the wake of a revolution, Eritrea has come to be ruled by a single man. Isaias Afewerki, who led a leftist guerrilla force called the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front during the Independence War, has held the presidency since independence was established. The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front has been reincarnated as a political party, the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice. Afewerki expressed support for a multi-party government before independence, but Afwerki’s People’s Front is the only political party allowed in Eritrea. The Country has no media sources independent of the People’s Front, so Afewerki wields total control of news coverage. Off the record, Samira and I joked how Afewerki was “maybe a president, maybe not a president.”

Plans to move Eritrea towards democracy have been indefinitely deferred. An election planned for 1998 and the implementation of a constitution approved by the voters in 1997 have been delayed indefinitely. In a 2009 interview with Reuters, Afewerki said, “I have never said that this a successful democracy.” Afewerki’s government denies that it has no desire to implement a constitutional multi-party government in Eritrea, maintaining that wars with countries like Yemen and the old rival Ethiopia make the country too unstable to risk a political reconfiguration. However, in Afewerki’s own words that he spoke before coming into power, “a one-party system will neither enhance national security or stability nor accelerate economic development. In fact a one party system could be a major threat to the very existence of our country” (President Isaias Afwerki’s Biography).

Samira’s father became involved in the independence movement as an intellectual when she was a small child. He had been a teacher before the conflict began. Samira told me, “my Dad didn’t go to fight, however he was helping recruit people to help with money or to recruit people to help with political things.” He was a member of a group in which each person was restricted to knowing just seven other members, so if a member was captured he or she would not be able to divulge the names of too many comrades.

The Ethiopian government, which of course controlled Eritrea at that time, caused Samira’s family great trouble to punish them for her father’s actions in support of the independence movement. Samira told me “He was imprisoned here and there. For example they would tell him “24 hours to get out of the city” so he’d just have to move, sometimes he’d just have to leave us somewhere and then later on we’d join him.” The government ordered Samira’s father to move around a lot. Their idea was to restrict Samira’s father to being in cities where he wouldn’t be effective for the rebels. He was imprisoned many times by the government and unfortunately he was tortured in prison several times: “they put them in cold water they put them upside down” said Samira.

I think that her father’s politics and the failure of the armed struggle to create an equitable Eritrean government influence Samira’s perspective on war. Maybe if her father had not been so involved in politics, Samira would not see her own experiences in terms of the larger events. But surely having a close family member who was so passionate that he would go in being involved after being tortured would guarantee that Samira would be political herself. The fact that armed struggle with Ethiopia led to a long, bloody war and a despotic government colors Samira’s skeptical perception of war.

Eventually, the fighting made living in Eritrea impossible. One day Samira was at school in the capital Asmara when planes began bombing the city intensely. Samira fled the capital with her brother as thousands of people fled the city. The two followed the flow right out of the city. She described that day: “people [were] fleeing anywhere they could. So we just followed the crowd… All the way out of town…because we didn’t know what we were doing.” Samira said that she doesn’t remember how many days she traveled, because they were moving day and night and it was difficult to think straight. They had no time to get their things or tell anyone they were leaving. It was total chaos.

Samira went to a neighboring city where they believed they would be safe, but soon that city was bombed as well, so they continued to flee. Samira said she would “never forget” how everywhere she went people told her to take off her red sweater, but she didn’t understand why until an older woman told her “[the plane] spots you in bright colors, it spots you right away.” Samira and her brother made their way North to Sudan. They walked half the way, then they got a ride from some Eritrean fighters on a truck they had to ride “like goods.” Samira not gone back to Eritrea since.

In Sudan, Samira had to contend with the threat of being kidnapped in the night by the Sudanese government, which sought to relocate the many Eritreans who fled to refugee camps in Sudan. The camps were located in harsh, remote locations where heat and thirst took many lives. Samira told me that her “neighbors, who were also cousins” suffered being brought to one of the refugee camps by the Sudanese government: “They would come early in the morning when you are asleep. You’re not even awake. You are sleeping. They took them. Two of the children died. It’s just sad. They couldn’t tolerate [conditions at the camp]. I was lucky, we were lucky.” In recent years, the Sudanese government, attempting to suppress a rebellion, committed an act of genocide against their own people in the Darfur region (Genocide in Darfur).

I can only imagine that being separated from most of her family and hiding from the maniacal Sudanese government must have been a difficult adolescence for Samira. She had already known a great deal of strife at that relatively young age. This is the age where most people start to think about politics and things like that, so her adult perspective on war must have been forming during this time. Clearly, Samira and her country were not benefiting from the conflict and the immediate view of it would not have yielded the kind of distance a person needs to have to romanticize a conflict. She must have been truly “sick of war” by this time.

Samira continued her education during this time with help from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. She completed high school on time, then went on to Cairo to study at a technical institute for secretarial work. She had wanted to study medicine, but that was not really possible because of her status as a refugee. She said “it would have been different” if the conflict had not happened. This is one more reason for Samira to be “sick of war.”

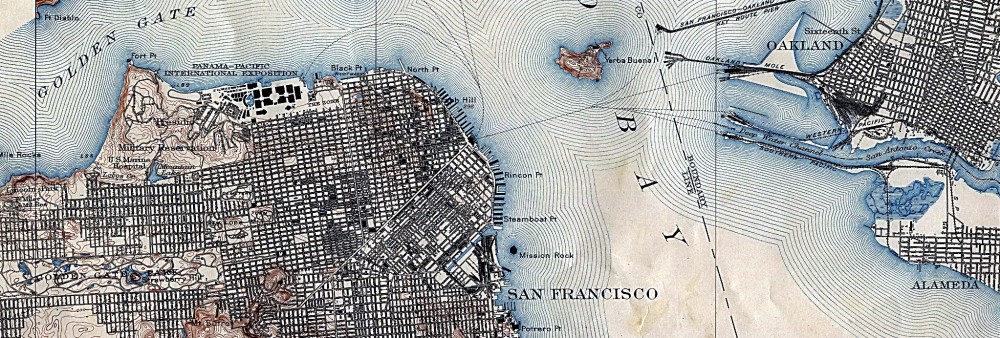

Eritreans weren’t allowed to work in Egypt, so she went on to Baghdad, but left because of the Iran-Iraq war and general dissatisfaction with being there. Even though that war did not directly affect people in Baghdad, she had had enough of being in war zones by that time. Samira came to the United States when she was 19. She lived in South Dakota for a while, then moved to San Francisco.

Samira was reunited with her family in the United States, as family members have left Eritrea over the years. Samira still has extended family in Eritrea, but no immediate family members remain in that country. It reminds me of how Edward Said said that his home Palestine became “a series of Israeli locales” (Said X) and how all of Said’s family and acquaintances were gone from Palestine. Samira was reunited with her father after being separated for about ten years: “I can’t even put a word on it. I’m so blessed.” Samira must have some trauma from the events of her childhood, but she has lived most of life in the United States in reasonable comfort and does not seem like an unhappy person.

In conclusion, Samira’s flight from Eritrea, her difficult time in Sudan and the despotic nature of Eritrea’s independent government made her dislike war as a political tool. Those who only experience war in movies and video games sometimes have romanticized notions of what war is like. They don’t imagine what a bombing raid does to an ordinary little girl and her brother. When people call for a bad government to be driven out by some freedom fighters, they don’t necessarily think about what happens when those freedom fighters become the next government. Now, as a reservation, I don’t believe that Samira feels that Eritrea should be a part of Ethiopia! What I am saying is that Samira stopped believing in the armed struggle. We talked a little after the recording stopped, and she said something that stuck with me: “peace for all the people is my mission.” When we were talking about the tensions between Ethiopia and Eritrea is asked her if parts of Eritrea “are still occupied by Ethiopia.” Samira said, “I think it’s an excuse for just…an ego of the government. It’s not to do anything with the people. They could live safely and peacefully, actually.” Samira doesn’t believe in fighting or in those so-called “freedom fighters,” who are now dictators.

Works Cited

“Eritrea.” Cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency of the United States, 3 May 2007. Web

Transcripts

Samira warns me that she speaks softly, then the recording starts. I am surprised by the sound of my voice. My additions to the conversation are written inside of [—] marks like [this]. My comments on what is happening in the conversation are written on the right side of two forward slashes like //this. Be aware that this is not intended as a word-for-word copy of the mp3 file. The goal is to capture the meaning of what was said rather than the exact words. What appears here should be considered my translation of the conversation from the language of conversation to the language of text.

Me: I’ll just put it [the recording device] closer to you.

Samira: [laughs] ah, ok.

Me: Ok Samira, I’m Thomas. So, tell me about where were you were born.

Samira: I was born in Eritrea; it’s a town called Abudat [SP?].

Me: Is that a small town?

Samira: It’s a city.

Me: In a valley?

Samira: No, actually it’s a low land. But I didn’t grow up there, I was just three months old when I left so I don’t know [the city].

Me: Why did you family leave?

Samira: Well, my dad was a teacher and also politically involved, so they [the government] were putting him from city to city [to impede his political activities].

Me: So, did you grow up in a particular town or did you move around with your dad?

Samira: I actually moved around. I didn’t grow up in a particular place.

Me: And you were going to school?

Samira: Yes.

Me: So, can you tell me about your father’s political involvement?

Samira: My father’s political involvement is a long story. You know about partition of Africa, right? So what happened was Europeans took all of Africa. Eritrea was taken by the Italians and was ruled by the Italians for about 50-60 years. And then in the second world war, Italy became allies with Germany the British kicked out [the Italians]. I’m making the story shorter!

Me: That’s fair.

Samira:.. kicked out..

Me: …the Italians…

Samira: … and they took over…

Me: …Eritrea…

Samira: They took over Eritrea for 17 years. And then what happened was, when all the other countries got independence, Eritrea did not. What happened was the British, or the Eritreans, couldn’t make up their minds.

Me: They couldn’t make up their mind if they wanted…?

Samira: There was a political thing; the US was also involved with that. They wanted to be part of Europea [Europe] and there were some Eritreans who wanted to be with Ethiopia. But when [Eritrea] was federated with Ethiopia without the people’s will, the Eritreans started movements. The teachers and students participated in demonstrations and stuff. My dad was a part of the movement.

Me: For independence?

Samira: First for the demonstrations and stuff. But then what happened was, when the brutality started [I don’t understand this part. It’s around 3:38.], Ethiopians took over, and people didn’t like that. They started grassroots movements called [the seven people?], everybody would know seven people so that way when someone got in trouble they…

Me: Oh, I see //this part isn’t clear to the listener: someone in the movement would know seven other people in the movement so that when somebody got caught by the government, they wouldn’t be able to divulge the names of more than seven comrades.

Samira: He was one of the people that started the movement, in 1961. He started to get watched; he was in prison, all these things. That’s how the trouble started. And after that, when more and more brutality more imprisonment and killing started, Eritreans stated an armed struggle in 1961. At that time what happened was that people went to fight. My Dad didn’t go to fight; however, he was helping recruit people to help with money or to recruit people to help with political things, so he was imprisoned here and there. For example, they would tell him “24 hours to get out of the city,” so he’d just have to move; sometimes, he’d just have to leave us somewhere and then later on we’d join him.

Me: Can you tell me a story about that happening?

Samira: Ok, so one story is this: [PORT] is part of Eritrea. However, it’s very far; it’s very hot. So they put him in 24 hours to go from the city to go to that place [the port]. So he left us there in the city because he could not get us to another city. He left by himself. There were others going there too.

Me: They were telling him to go to this port town?

Samira: To port town. For example, he cannot move from there. He cannot go anywhere. [Father’s birthplace] is his birthplace; they told him he cannot get there; he cannot go to that city. He can go to work, but he cannot move from that city.

Me: He was being kept in the port? He was arrested in the city? And you were with separated from him with your mother?

Samira: Yes, with my mother and two siblings; others were not born. So, after a year and a half or so we joined him in that port.

Me: how old were you when this was happening?

Samira: Hm, when this was happening, I was eight years old. So, we went to there; however, it’s like the climate is harsh so my mother was sick. So we, my mother and me and siblings, not my father, we moved to Ethiopia. It’s not far away [from the port]. Later on he could go to [Ethiopia] but that’s the only town he could go to.

Me: Yeah. So, you were right across the border, and you dad was in this port, and the government didn’t want him to leave this port.

Samira: Yeah, however, they allowed him to that city in Ethiopia because it was Ethiopia it was not Eritrea. Any Eritrean city he could not go in. So, when we would go to Eritrea, we were kind of smuggled. We would go see my grandparents.

Me: How exactly did they smuggle you?

Samira: Well, we would go from Ethiopia; nobody would know. However, when we got to [Asmara?] everybody knows everybody, so they would not say, “they are the kids of so and so,” because that’s how you were known, as “the kids of so and so.” There was curfew there. At six, we would go just right before the curfew and stay in my grandparent’s house and if we had to see another family we would go just before the curfew and not tell anyone that we were coming to stay there for a week or so.

Me: Where were you going?

Samira: To Eritrea. To see my grandparents and uncles and cousins. We would go there, go, go, go, and come back to the city where my parents were born.

Thomas: So then, uh, you must have grown up moving from place to place as your father was getting told where to go, I guess they wanted to restrict his political movements so they were telling him where to go?

Samira: Exactly.

Thomas: What about when you were a teenager?

Samira: Ok, so now…a teenager…I’m like 12, 13? So, when I’m 13…what happened was…when I was 13, the Ethiopian government was overthrown. It was the <<can’t make out, sounds like name of leader who took over>>… It was a communist country, Ethiopia. So, kind of like my dad’s restriction going to Eritrea, was kind of lightened; like he could go Eritrea! But not to his birthplace, but to Asmara, the capital city of Eritrea. So we went there, like he want[ed] to move, so we went there and there was war and stuff. It’s like one day me and my brother, we were like at school…my younger brother…and we couldn’t go back to our house.

T: Why?

S: So…what happened was like…there was bombing and stuff…so we just moved with the crowd, we just went with the crowd. We didn’t know where we were going; we didn’t know what we were doing; we just like…because we…in Ethiopia, when we were there, when the revolution was there, there was also war and stuff, but not bombing. So, we really didn’t know the exact what was going on. So, anyways, what happened was we went to a city by foot…I don’t know how many days we traveled. At first daytime, and then at night.

T: You were fleeing the capital because of the fighting there?

S: Because of the fighting…because of the bombing. The bombing was not only in the city, but the city that we were going to, it was bombed also. We didn’t know that. Nobody knew that, but it’s like the planes and stuff, you know, and people, I think were accustomed <<?>> There was this older woman.

One thing I’ll never forget: I had a red sweater on and like everybody shout[ed], “take the sweater off, take the sweater off,” and I didn’t know what was going on. So this woman came in and took out the sweater, because it’s bright color; it spot you right away…the plane.

Anyways, we got to another city called Keren and that happened to be my parents’ birthplace…

T: When you fled the city, was that immediately when you left school that day or was this more…

S: It was bombing, so it’s not like school was let out, but we have to go; we have to leave. So the thing is our house…and it’s like people are fleeing anywhere they could. So, we just followed the crowd.

T: So you just ran out of school and followed the crowd all the way out of town?

S: All the way out of town…because we didn’t know what we were doing. So, anyway, when we got to the city, it is like everybody is ok [with] what you guys [are] doing. It’s like people are so kind and stuff and they’ll ask you and we say we don’t know where our parent are; we were just at school. Kind of everybody ask[s] you whose daughter or whose son, it’s a small community. Everybody knows everybody. If you don’t know me, then somebody else will know me. So they asked someone and they knew; they came and they took us to their place. Still, they are scared because still the bombing is going on.

So anyways, so it kind of start[ed] in the morning and there was a lot of people who died in the bombing. Actually, somebody I know lost three daughters.

Then, after 15 days staying [in] that city, we decided we couldn’t go back to Asmara, to the capital, so what happened was…

T: So you left all your things in Asmara

S: Oh, yeah, nobody can get anything. So, we decided, somebody, that it’s not going to be safe, so they contacted our family; like, they contacted my mom, my mom.

T: They must have been worried about where you were?

S: Oh, yeah. They didn’t even know where we were, and there’s so many people died. At the same time that my dad was also in prison. That’s why they contacted my mom. So, my mom was like, whatever you could do, you could help them. We went to Sudan by foot…halfway. And then halfway the freedom fighters, they had this lorry that they take like so many…it…we were good

T: People had questions if you were good?

S: No, no, no. We were up, we were on this van, this lorry.

T: Oh, you were riding…a truck?

S: A truck, yes, like we were goods…everybody’s on like everybody there are so many of us.

T: Were you riding on top?

S: There were other people outside the truck. Some people were just holding outside on the truck. If you were lucky, if, you were inside the truck.

T: So, when you were walking from Asmara…and then you walked toward Sudan.

S: We stayed in that city, Keren, for 15 days first. And then we walked halfway to Sudan, and then halfway on that truck.

T: And were you still with other students?

S: We didn’t know. I don’t know if they were students but there were young people. Because we were new at the <<??>> we don’t know. Because we knew…when the bombing started everybody just fled in all directions.

T: So it was just you and your brother looking out for yourselves? The adults were nice?

S: They were nice, but we don’t know them actually. We really didn’t know them.

T: They gave you food and water?

S: Yeah. When we were from the other city, we didn’t have any food. When I say we didn’t have food it’s like, we had just like minimal things like you would get from the villagers. Everybody give you but you don’t even feel like eating. And most of the time, we are trying just to go. But in the city we had food and everything, and after that…so we couldn’t go back to Asmara, because the thing got worse; there was no bombing. But the chaos and the killing continued.

Now, the people who took us from that city, so people who we know…we didn’t know them but our family knew. So we’re going toward to Sudan. Halfway we walk, and then halfway we got the truck. We went to a refugee camp in Sudan.

We stayed in the refugee camp about…how long? Not quite a month. Then UN came…

T: Was there enough food?

S: Not to start. Not the ideal food. There was food. But not the type as here. You just don’t…we were not poor. We had food…

T: At home, but not in the refugee camp?

S: It was not enough; it was not appetizing.

T: So, I’m wondering, when you fled the city and were heading to Sudan, when you came to a village…what would happen when you came to a village…would everyone be fleeing and go on the road with you?

S: No…people in the village stayed there because the villages at the time were liberated and were not under Ethiopia, but under the rebels, the freedom fighters. They were always afraid of the bombing and stuff because everybody else would be hiding. Some of them might, but some of them not.

T: Why did you decide to go to Sudan and not stay in one of the villages?

S: Because, as I said, it’s not stable. You never know. The other thing also, is like…I don’t know. Everybody else was doing it. You’ll end up fighting too.

T: It was safer to go to another country?

S: It was safer.

T: So, you stayed in the United Nations refugee camp in Sudan for about a month, and then did you go back to your parents or did you go some place else?

S: No, our parents were still in Eritrea. What happened was the UN was opening a high school in Sudan, in Kassala, so they took us to Kassala…it’s a city in Sudan that borders Eritrea. There are many Eritreans there; they have been refugees for a long time…probably since the ‘60’s, since the war started, or the conflict started.

So, we came there and my brother went to middle school. I went to high school. They were giving us, usually they called it Unesco…it was not ruled by Unesco; it was run by the UNHCR.

T: When you were in Sudan, did you feel alienated from the native people in Sudan?

S: There were so many Eritreans refugees there; it’s bordering Eritrea. There’s always inter-marriage, you know, family here and there in both places. On the border you know how it is, many are relatives. Especially in that areas there are so many refugees for a long time, so, it’s like so many Eritreans were there already.

But, but, what was happening in the Sudanese government was always threatening the refugees. You cannot be in the city; you have to go to the refugee camp. It’s like always you’re on the run, always you’re in the hide. Even though we have papers for the UNHCR, still we are afraid that somebody will take us to a really, really bad places, very, very hot places, that has nothing, not even stable refugee camps.

T: The government tried to put the refugees in the most inhospitable places in Sudan, in the middle of the desert. No water.

S: Exactly. Yes. That is exactly what has happened to many unlucky people. I remember at one point, one year that we did that so many people died, especially…there was really high…

T: High temperatures, not enough food, not enough water?

S: Nothing, nothing at all. Very remote area.

T: It was not violence but the conditions.

S: Yeah, it was the conditions. We were lucky.

T: Did you experience this yourself?

S: No, I did not experience myself, but I knew about it. My neighbors who also happened to be my family…my second cousins…they took them to Abroham <??> a very remote area. They would come early in the morning when you are asleep. You’re not even awake. You are sleeping. They took them.

T: Kind of kidnapped.

S: Exactly, kidnapped. Two of the children died. It’s just sad. They couldn’t tolerate. I was lucky; we were lucky, didn’t get to that.

T: Did you complete high school there?

S: Yes.

T: When did you learn English?

S: In Eritrea or Ethiopia, you start taking English as a subject in 2nd grade. When you are in middle school all the subjects are in English. That’s how I started learning. In the UNHCR schools all subjects are in English. We had to sit for GEC, compatible to English school if you passed.

T: Were you working? And did you reconnect with your parents when you were in high school?

S: Yes, my last year in high school, my mom and my three siblings came to Sudan. They had to flee. My dad was in prison so they had to leave the country. They couldn’t go to school and my mom was tortured…they would come to the house and take stuff. She didn’t know where my dad was in prison so she had to leave the city. I saw her briefly there and then I had to go to another city to take the exam for the GEC, the General Education.

While I was there after we finished the exam, I just stayed in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. I stayed there about three months and UNHCR was also giving scholarships for Egypt and Kenya. They told they want us to apply to get scholarships. So we applied…they just give you a general English exam that you can pass. So I passed both for Kenya and Egypt but then Egypt was business secretary school and the one in Kenya was for nursing school. But then my friends were going to Egypt so I just go…I don’t have nobody to go with me to Kenya even though I want to do something medical field. I just went them to Egypt, to Cairo.

T: You went to Cairo and started university there?

S: It’s not university. It’s an institute for studying secretarial business.

T: It would have been tough to focus on school while you’re running from all the violence…yeah?

S: That’s very true. It’s been hard but the thing is doable. You also want to try because our father and mother wanted education so bad. They educated themselves, not universities and stuff, but still education was so valued…they value education. They instilled that in us. Even in the refugee camp, you just read. In Sudan, I’ll tell you, in Kassala, we have electricity, but you pay for electricity…but we have to say hi to my teacher.

<<interrupted by teacher in 33:40 — 32:30>>

T: Seems like you have a really good relationship with all your former teachers.

S: They are amazing. I mean, I love my teachers. Even from my childhood. My dad was a teacher.

T: He would have had to stop teaching with the political thing started, when he got involved in politics.

S: I mean, when he got out…he’s here now…yeah, I saw my dad after 11 years, 12 years…

T: I asked you, it must have been difficult to study because of the violence and then you started to talk about the electricity.

S: You pay for the electricity, no matter what. The problem is this: no electricity most of the time, we don’t get electricity…and it goes dark all of a sudden. We have to put kerosene and we have to study hard. Let me give you an example, for history: Compare the American Revolution to the French Revolution. It’s an essay, it’s not like ABC and whatever like you can give.

T: I’m not sure if I would pass that question.

S: (Laughs) I don’t know. No American will pass history. I’ll give you that. That’s what I tell my daughter. I’m being judgmental.

T: It’s sort of true. Even though I’m American, I’ve lived here my whole life, there’s just so many basic things that I don’t know about my own country. It’s embarrassing a little.

S: That’s OK. You know they give you a citizenship exam and I don’t know if any American would pass it. That’s what I tell my daughter. When I say American, I mean anyone who was born here and my daughter was born here.

T: I saw some studies where they asked Americans from the exam and it was abysmal scores.

S: So yeah, we have to study, like oil, it’s lights…we still pay for electricity.

T: So you went to Cairo and study at the institute for secretarial business…

S: It’s a language school, and international language institute but it’s a comprehensive school…it has language, secretarial, business college. Ours was a combined business, secretarial.

T: So you were not able to study medicine.

S: I was not able to do that over there.

T: Do you think it might have been different it you didn’t have to flee from Eritrea?

S: Yes. It would have been different.

T: You managed to avoid getting kidnapped.

S: Yes. It was sheer lucky. We were sleeping here next, and the next door people got taken out, they would go. It was always fear.

T: We had this book about illegal immigrants that has this quote about how the people are afraid of being picked up by the INS and ICE. You must be deal with all the time in your work with asylum seekers.

S: Yes, that’s true.

T: Did you finish the secretarial school?

S: Yes…some of my subjects were transferable here to City College.

T: Was your father still in prison when this was going on?

S: When I was in Egypt? Yes…

T: He had been in prison continuously?

S: Yes.

T: I don’t want to make you talk about things that are too painful, but you said your mother was abused and your father must have been abused in prison.

S: Oh, yes…torture. Torture…he talks about it now. They put them in cold water; they put them upside down.

T: And your mother, did she follow you to Egypt or stay in Sudan?

S: She stayed in Sudan.

T: And were any of your siblings with you in Egypt?

S: Yes, actually one of my brothers was there. He went there on his own from Sudan.

T: He was an older brother who had had already been there for a while…

S: No, not the one that went with me, but another brother. We’re six siblings…I have 1 sister and 4 brothers. One of my brothers went to Egypt on his own. This one was on his own, he flew there from Ethiopia. And then my sister came when I was there…I went to Sudan and brought her to Egypt.

T: When you finished at the institute you must have started looking for work.

S: Yes, but in Egypt you cannot work because you have to be an Egyptian citizen. They are very strict. However, because the UNHCR school had some kind of connection with like they were training us with different companies. The companies didn’t employ us; they take us as trainees they give us some pocket money. The UNHCR was giving us some money too for the education and to survive.

So, after we finish, we have to go somewhere, we cannot stay in Egypt because our student visa expires. Even though we were refugees still we couldn’t live there.

T: How old were you at this time?

S: I was 18, 19.

T: You had to leave Egypt because of the rules. Where did you go? Were you thinking about going back to Eritrea at this time? Was the fighting stopping?

S: No the fighting was still going on. The US and Canada were giving resettlement if you apply. I didn’t want to go far away. So, I went Baghdad to go to university. Stayed there a month or so. But it was not for me. So many things.

T: Everything was different. Language was probably different?

S: No, I knew Arabic. I speak Arabic. It’s not the language, but the political thing. Iraq at that time was good, many Eritreans there…I don’t know…

T: The weather?

S: No, Iraq is beautiful; the weather is beautiful. Baghdad is very beautiful…

T: Something about the culture…

S: I can’t pinpoint exactly…

T: Because you didn’t have family there?

S: Probably. But the other thing there was the Iraq-Iran war. Baghdad was not affected that much but still you could feel the…I was sick and tired of war. So I came back to Egypt again…so, it’s like, where to go? Like nowhere. Did have a choice, so I applied for US resettlement. Got accepted and came here, and went to South Dakota.

(laughs)

The funniest thing is at the UNHCR office in Cairo, Americans like, “Where are you going?” “I’m going to South Dakota.” And the Americans…not anybody else…”South Dakota!?” As if I’m going to the moon or some place. This was 1985.

It’s different there now. At least you can see diversity there now, but when I went there…

T: You must have been the only African in town.

S: Yeah, well, I was not even in town. I was on the outskirts of Sioux Falls. I was not the only African; I was the only colored person there.

T: Was it kind of awkward? Were people really racist there? Or just confused?

S: There were some of the nicest people there. They would go out of their way to do stuff, but they were not racist. They were confused. That’s how I would put it. I would speak English and they would ask, “How do you learn American?”

T: How did you learn our obscure unknown language? (laughs)

S: Exactly! (laughs)

My favorite thing is this…I would be eating…and I’m a Muslim…I would say “Insha’Allah,” the name of god. That’s what you say when you start something. And they’d say, “Pardon” and I would say I’m just calling my god. Oh…she’s not even Christian and she knows about god.

T: So, it’s probably like everyone goes to the same church in this town.

S: Yes.

T: The people were nice but you decided to leave South Dakota pretty quick?

S: I decided to leave South Dakota pretty quick not because of the cultural but because of the weather.

T: It was freezing

S: It starts at the end of October, the first of November, the thing just changed, like over night like freezing. So by the 10th of November, I have to…I came here actually to visit a friend.

T: You came to SF to visit a friend?

S: Actually to LA, to Orange County. My cousin joined me [in] South Dakota. I stayed there about three months. She was there about 10 days. We came here to visit a friend but the weather was so good. I had a friend in SF and I told my cousin, “I’m going to visit.” We just made up our mind; we’re staying here; we’re coming back here. We went back (to South Dakota) and we came back here. When we came back here, I told my cousin, “I’m not crazy about Orange County for me. SF is the perfect place.” I found a place. My place is here.

T: Yeah, this is a great place. A lot of immigrants end up here. I’m one of the only people I know that’s born in San Francisco.

S: You were born in SF? I have a couple of people who were born in SF.

T: I probably have one of the most boring life stories.

S: No, San Francisco…you have a story. Trust me. Believe me.

T: You haven’t told me about any jobs. You were maybe 20 by now and looking for work.

S: I applied to this place and accepted in South Dakota. But I have to leave. So I came here in San Francisco; I got a job at childcare.

T: Did you have work in South Dakota?

S: Yes, childcare…but I was accepted at nursing school. But I moved here because of the weather. So I came here, worked in childcare. They told me to get PPD testing (TB)…a skin test for TB. I went to refugee clinic to get the PPD test and as I was talking to this lady. She’s a nurse, and she said, “your English is good, and we are looking for an interpreter and someone for our pre-natal program, the doctor wants an assistant.” I said, “I have no medical training but, yeah.” She said they train me. So I applied there and I worked there almost 10 years.

What I was doing at the refugee clinic…I was working at the pre-natal program doing vital signs. Refugees from different countries come, but I was responsible for Eritreans and people who spoke Arabic.

T: So you speak Arabic, but I don’t know what language you speak in Eritrea.

S: I speak Arabic, Tigre…in Eritrea we have 9 different languages. So I speak Tigrinya. I was taught Amharic in school. I speak Tigre, Harari, Arabic and English.

T: You speak five languages fluently?

S: Yes…well, if you think I’m fluent in English, then, yes.

T: I noticed you’re wearing a jacket. Do you find it cold here?

S: No, it’s not cold. I’ve been here 30 years, so I don’t when it’s hot. But my body is always cold. Not because…it was windy outside. I’m always cold.

After that I found a job at UCSF Aids project. I was doing HIV triage and counseling.

T: Was it people who just contracted the disease?

S: No.

T: Why was it triage?

S: We will get calls and prioritize this person, this needs. If somebody calls me and says “I’m HIV positive,” I tell them where to go. If somebody calls and says, “I want to get tested,” I tell them to go. I was coordinating. We have nine different sites, so coordinating that. I worked there about 10 years also. Then I got sick and surgery on my hand. I had nerve thing. It was painful, so they had to surgery. After that I had some health issues, so I didn’t go back to work. So I was laid off, also because of funding stuff. I had priority hiring but I couldn’t go back to work for a while.

T: That brings up to the present? You have family in the US?

S: Yes, I live with my daughter and my husband. My family were living in different places, some in Sudan. First, I brought my two brothers, and then my mom, and then my other two brothers. And my sister in Cairo. And the last person I brought to the US was my dad.

T: You told me your dad finally got out of prison after about 10 years. Were you about 30 then?

S: I don’t know…I’m not not good at the timing now. I don’t know if it was the whole ten years. In the time we lost contact. We heard about him from other people. He contacted us.

T: He was free for a little while and then managed to contact you again. And did he come to the US?

S: Yes, after a while. It was a process. They have a family reunification.

T: What was it like seeing your dad after so long a time?

S: I can’t even put a word on it. I’m so blessed.

T: And there’s been continued fighting in Eritrea and Sudan. Has that impacted you since you left Africa?

S: Yes. I don’t have immediate family there but I have cousins and uncles. I have friends. The things is this, Eritrea got independence in 1991 and was recognized as an independent state in 1993. However, right now, the people who were fighting to liberate it, supposedly, are the one’s who are torturing the people. Right now, my story might be like nothing compared now to the thousands and thousands fleeing the country. They were kidnapped from the refugee camps. They’re being sold to the Bedouin in Egypt. And they’re being sold to organ traffickers, their organs being sold. They are being asked to pay $50,000 to get out from the capturers. It just continues. The cycle, the violence just continues.

T: There are still some parts of Eritrea that are occupied by Ethiopia?

S: There’s a border in conflict about it. Whose is this town; whose is that town. I think it’s an excuse for just…an ego of the government. It’s not to do anything with the people. They could live safely and peacefully, actually.

T: Do you think Ethiopia wants to control Eritrea because of the Red Sea?

S: Ethiopia doesn’t have a port, and Eritrea has two ports. Yes, some Ethiopians really want the port of Assab. There are some who say openly that in the government right now. They say they don’t [need] Assab because they are using Djibouti. But it’s easier for them to use Assab. But right now, Assab is a ghost city, not even used by Eritrea. It’s so sad because that port was very alive and very…

T: That’s the place where you separated from father for a while…

T: Do you feel like an exile from Eritrea? Did you have to leave?

S: Of course. There was no choice. I was not given choice.

T: There was day the bombing…

The mp3 Ends here. We continued talking for a couple minutes. I remember she said “my mission is peace for all peoples.”