Memories of an Émigré

by Levan Tortladze, May, 2014

The United States plays many roles in an émigré’s life: it is a roof, an umbrella for protection and safety over the heads of people who come from all over the world; it is an opportunity for financial success; for some, including but not limited to activists and people with marginalized social identities, coming to America is the only way to survive. But successfully immigrating into the United States and then maintaining a life here isn’t as easy as most immigrants like to believe. Adriana, a 34-year-old wife, mother, student, immigrant from Brazil, and a resident of the San Francisco Bay Area for thirteen years, with a pending U.S. citizenship, she shares in a two-part interview what living – struggling and eventually succeeding – in America was like after 4-month-long bureaucratic process of applying for a visa and leaving all she knew, her family, and her language, behind. “My perception before coming here was that this country was very developed in the sense that there was no homelessness, no poverty, and, most of all, the streets and environment were very clean. California has carried the myth of easy success and vast opportunity. For centuries, immigrants have followed this myth. However, when I moved here, I was shocked by the poverty. I believed that the American Dream was real and easy.” Minot State University’s Andy Bertsch states in his study “The Melting Pot vs. the Salad Bowl: A Call to Explore Regional Cross-Cultural Differences and Similarities within the U.S.A.,” that “each nation has a distinct prism through which it views the world” (Bertsch 132). Just as Adriana’s narrative illustrates, the belief that all would be immediately well once reaching American soil is common in most countries around the world. Adriana continues to explain in her interview that her time in the United States has been far from easy. Yet, now she considers her plight a success story and pays tribute to the years she struggled as a new immigrant for her current happiness, her community, her family, her education, and general sense of accomplishment. Though Adriana’s personal journey to this place, both physically and emotionally, was full of “challenging times, loneliness and disappointment,” it is the process that made her successful, and it is people like her that make this country a success. Adriana’s story challenges the myth that all who come here are successful and wealthy, and are treated fairly, otherwise known as the American Dream. It can be said that the hardships an émigré experiences in his/her process of achieving citizenship are what actually help us realize that dream and achieve success.

After obtaining a visa, the funds to travel and move, and the courage to leave all that is familiar behind, surviving in America is full of difficulties: anxiety, pressure, depression, fear and stress. It takes a lot of time and effort to land a job that can support one’s basic needs in the host country while also supporting family at home. And as if that weren’t enough, one of the biggest difficulties in assimilating to a new culture is attaining the knowledge of the language so that one can adapt to both professional and casual society. Moreover, not too many people are fortunate enough to come to this country with proper documents and those who are undocumented, the constant fear of deportation haunts them. Even when a person gets sick and needs medical attention, his or only option is to stay indoors and self-diagnose, medicate, and treat via non-traditional methods, because medical care is not consistently awarded to those without papers. Adriana tells of times she was taken advantage of by employers, looked down on by social peers, discriminated against at every turn, frustrated with the language, and paralyzed by the constant fear of authority and deportation. She describes this 8-year period in her life as “really exhausting and lonely, living on survivor mode.” “The culmination of stressors associated with constantly having to adapt to unfamiliar environments, work-related stress, and lack of social and emotional support may take a psychological and physical toll on many transmigrants” (Furman, et. al. 168). It is difficult to move from one’s natural habitat, one’s home, to an environment that is completely different, with a different language, different rules, different social expectations, and even different food. Adriana explains that the sheer differences in her culture and this new American way were almost the most anxiety-producing. “Thanksgiving celebrations or other holidays were hardest for me. During these events, I felt like an outsider, like it was obvious I didn’t belong, like I didn’t belong at the party or at the grocery store near the frozen turkeys. Maybe, because I didn’t quite understand the meaning of the celebration, I just couldn’t get as excited as everybody else around me. I didn’t get it, and I didn’t even know how to begin to get it without announcing that I was that girl who didn’t know what Labor Day is.” But Adriana would soon realize that most people were more than happy to explain the history of the holidays, once she got over feeling nervous about asking. “I realized I’d only get out what I put in. My point is, it’s so important to learn about the new culture one is immigrating to. I just needed to get over myself, to let go of my own culture in order to embrace this new one.”

Furthermore, isolation becomes a major side-effect of the émigré. Lost and alone, one struggles to adapt even beyond job searching and money earning when he or she doesn’t have a community on which to rely. The fact that one’s closest kin is many miles away is often enough to make that person give up, regardless of his or her sacrifices, and go back home. “This lack of social and emotional support may force transmigrants to rely solely on themselves” (Furman, et. al. 168), which is probably the biggest culture shock for many émigrés such as Adriana. She tells of a time in which all these differences converged in a single dinner filled with her good intentions: “Some years ago, I remember, me and my husband moved into a new house in a new neighborhood. Just as is the custom in both our cultures, we wanted to get to know our neighbors and so [we] invited our next-door neighbors over for dinner. I prepared everything. After good food and a lot of wine, both my husband and me were satisfied, even proud of our progress in adapting to this new society. We called it a night, still laughing together and toasting one another. In my husband’s culture [Georgian], after a good feast shared with new friends, the next day is followed by eating more to help get over last night’s fiesta.” Basically, as Adriana would further explain, it is customary in Georgian culture for the partiers to reunite the next morning, hung-over, and eat comfort food while they continue to bond and get to know each other. But what happened next truly solidified for Adriana and her husband, who had felt so proud of their assimilation, just how far from home they were and just how different they were. “When we invited the same people back over, we were alarmed when police officers arrived at our front door, with a statement from our neighbors accusing us of having some kind of agenda, an evil ulterior motive to be inviting them two days in a row,” says Adriana, with disappointment in her voice. Her attempt to share her own culture in this new and foreign place had backfired. She states, “It was then we were convinced that some things are meant to be left alone.” What she felt needed to be left alone, as she would clarify, is her need for community, for belonging. She came to learn that that is not so natural here in the United States, at least not as it is in her hometown of Rio de Janeiro. Not only did she already feel isolated from her family and her culture, but she now had bad blood between her and her new neighbors. But even in this sad situation, Adriana feels something positive came of it when she says, “I became more independent. I trusted people less. But I was better able to weed out the people who would be my greatest friends from everybody else. It was from moments like those that I now have this amazing, strong, solid community that my husband, son and I have now.” As Adriana elaborated about her community, she can now rely on them and speaks of them as if they are more family than friends. Truly, just as Adriana’s isolation and disappointment led to her current support system, an émigré’s hardships do shape the person and, thus, the country.

Furthermore, America is a more individualistic society, meaning that individuals generally focus on his/her own goals and successes before those of his/her community or country. People come from all over the world to achieve their goals and at the end it ties into discovering their sole identity. On the contrary, countries like Brazil, where Adriana is from, are more collectivistic, meaning that people have a sense of common wealth and togetherness. They feel that they are merely small pieces of a bigger picture. Adriana claims she is very family-orientated, whether those family members are immediate and extended. She knows what it means to be a part of a bigger picture in which people have solid support system anywhere there is family. At first she experienced a culture shock. Being raised in such a manner, she recalls working at a restaurant as a waiter, where it is known to have lots of undocumented immigrants working under the table.

“I was always picking up slack for other workers as well and helping them out, but once people started noticing my behavior, they started to take advantage of that situation. Whether it was my job responsibility or not, I was always the first person to be asked to stay longer hours. It started becoming a routine, which sometimes caused me to quit the job because I was overwhelmed with extra responsibilities. Slowly, as time went by and I acquired some experience and knowledge on how to deal with such situations, I became cold and immune to such demands. Once I started to notice that people were slacking due to their personal lack of will in completing the task that they had been hired to do, I was unwilling to pick up their slack. Me, coming from a nurturing environment, where it was not a question whether I was going to step up to the plate, but a mandatory obligation. Which is unusual in my culture, and made me feel guilty and ashamed. This could have been the beginning of my assimilating to this country and its culture.”

It was against Adriana’s nature to think only of herself, but she had to in order to succeed. She had to not feel and be selfish to self-preserve. “A ruthless individualism, expressed primarily through a market mentality, has invaded every sphere of our lives, undermining those institutions, such as the family or the university, that have traditionally functioned as foci of collective purposes, history, and culture. This lack of common purpose and concern for the common good bodes ill for a people claiming to be a democracy. Caught up in our private pursuits, we allow the workings of our major institutions—the economy and government—to go on “over our heads” (Andre Velasquez). Instead of feeling like she was a smaller piece in the larger picture, in America’s individualistic society, Adriana felt like she was more of a pawn in the game of people more important and successful than her. But even this she credits for her current happiness.

“I created a community and family that I really care about and that are closer to me than my own family at this point. After years of challenges and obstacles due to my illegal status, I finally got to work on my education and be a mom, wife and productive member of the society that I once resented. I would say that if I never got to legalize my situation in America, if I never overcame all those obstacles, I would always feel a lack of purpose or accomplishment. I think I would have always felt more disappointed in myself.”

America is filled with immigrants who hold the same mindset. These people, who come from all over, endure their struggles, and can and do end up successful. Sometimes one’s definition of success evolves over time, but America is made up of strong, dedicated immigrants, and that is why the American Dream is still alive in the minds of people everywhere.

It is true that immigrating to the United States is challenging as many émigrés are forced either by oppression, discrimination, financial struggles, or just the difficult search for a much-dreamed-about American identity. A country that is well known for standing up for its people and providing basic human rights tends to be inviting for many immigrants. Adriana tolerated being pushed around at jobs and her life was in the hands of her superiors, who didn’t care a bit for her well-being. After living in conditions that were barely tolerable and constantly being exploited, she still contributed so much to support her family back home. After all her hardships she still claims that those very hardships made her an even stronger person today.

Works Cited

Bertsch, Andy. “The Melting Pot vs. the Salad Bowl: A Call to Explore Regional Cross-Cultural Differences And Similarities Within The U.S.A.” Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict Volume 17 (2013): 131-148. Print.

Furman, Rich. “Social Work Practice with Latinos: Key Issues for Social Workers.” National Association of Social Workers Volume 54 (2009): 167-172. Print.

Andre, Claire and Manuel Valasquez. “American Society and Individualism.” American Society and Individualism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1991. Web.

Transcript

Levan T: What is your name?

Adriana: Adriana.

Levan T: What year were you born and where?

Adriana: I was born in 1979, in Rio de Janeiro.

Levan T: Could you describe a little about your household?

Adriana: I lived with my mom and grandmother, for a while I had my uncle and his family living with us.

Levan T: Can you tell me a little about your living situation in your country at that time?

Adriana: Growing up in Brazil was fun. Spend a lot of time in the beach and was blessed with lots of sunny days. However in my situation I always felt that there was something else for me to: “I always dreamed what it would be to live in a different country and because of American culture being very popular in Brazil through music”. I thought about America most.

Levan T: Has it ever crossed your mind that one day you would immigrate to U.S?

Adriana: I always dreamed about.

Levan T: How old were you when u came to U.S?Adriana: I was 21 years old

Levan T: Could you describe a little about how did you manage to get a visa or how was the traveling to this country?

Adriana: First I asked my mom, if she would be willing to not paying my college tuition for one semester and instead pay for my travels in California.

Levan T: What was her reaction?

Adriana: As a mother, it was only natural for her to be concerned about my postponement of education, but it was obvious to her that I’ve wanted to do this for a while.

Levan T: have you heard about the immigration in California?

Adriana: California has carried the myth of easy success and vast opportunity since nineteen century, when gold rush took place. For centuries immigrants follow this myth, as gold brought explorers form all over the world. California attracts immigrants looking opportunities to express their ideas more openly. California inspired many movements that iconize the hippies form Height Asbury, gay community of Castro Street and Sexy tan bodies from Los Angeles Beaches. Now Californians continue to witness a wave of immigrants who come to the golden State looking for freedom to express their minds, sexuality and politics views making California an exciting state, motivating ambitious young minds looking for freedom and success.

Levan T: what was your perception about U.S prior to coming here and after being here?

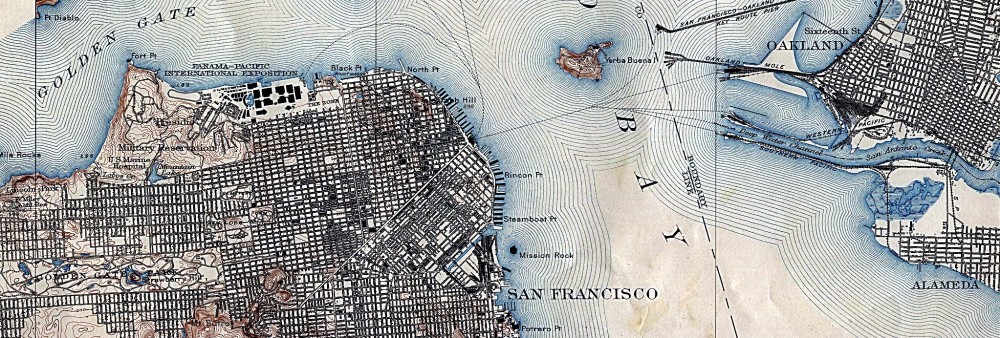

Adriana: My perception before coming here was that this country was very developed in the sense that there was no homelessness. No poverty and most of all street and environment were very clean. However after I moved to San Francisco, I was shocked by the poverty I witnessed among the Market area. But also fell in love with the beauty of this city and cultural diversity I found in the mission district.

Levan T: Have you heard about other immigrants?

Adriana: it is the big issue of conversation, here in California there are the huge amount of Illegal immigrants. The bed economy in Mexico motivates Mexicans to cross dark, cold and dangerous trails to cross the San Diego border. In Mexico it is extremely difficult to obtain an American Visa, and crossing the broad becomes the only chance to arrive in the USA and possibly build something better then what they left behind.

Levan T: what steps did you have to follow to apply for a visa?

Adriana: I had to pay some application fees, schedule an interview at an American embassy and prove financial status and reasons that would not keep you away from home.

Levan T: How long was the process?

Adriana: About 4 months

Levan T: What kind of visa and how long was the permit.

Adriana: I received a 10 year visa tourist visa, but I could only stay for 6 months legally.

Levan T: How long have you been here?

Adriana: Overall I’ve been living in California for 13 years.

Levan T: How has living in California impacted your identity?

Adriana: California reminds a bit of home because of its warm climate and more flexible and open minded community. But after all it is still an American culture and it was difficult to adapt to individualism way that is predominant. Therefore I felt that I was becoming a little bit selfish. On a positive note I learned and started to admire how the system worked if you were privileged to have legal status.

Levan T: what was u hoping for in California? Could you please be more specific?

Adriana: Many immigrants choose to come to the United States for better quality of life and more work opportunities. This was the dream country for lots of emigrants looking for opportunities to express their ideas more openly. When I got here we some help from government side, lot of agencies were working, and lots of people were also trained to help emigrants.

Levan T: Tell me about some moments where u felt isolated? Or when someone made u feel isolated.

Adriana: Thanksgiving celebrations or other holidays. During some of these events I felt being an outsider. Maybe because I didn’t quite understood the meaning of the celebration. Which brings me to the point of how important is to learn about the new culture one is immigrating to.

Levan T: Could you tell me of a time where u felt confusion at work?

Adriana: I was always picking up slack for other workers as well and helping them out, but once people started noticing my behavior, they started to take advantage of that situation. Whether it was my job responsibility or not, I was always the first person to be asked to stay longer hours. It started becoming a routine, which sometimes caused me to quit the job because I was overwhelmed with extra responsibilities.

Levan T: How did your struggles and fears, helped shape you?

Adriana: I think that all the challenges I had during my first years as a new immigrant helped me to appreciate what I have today. It made me an open – minded person to except other culture and their costume (even if I don’t like)

Levan T: What good came of this hardships?

Adriana: A great family, friends, education, quality life and a full life experience.

Levan T: how is your relationship with other Americans?

Adriana: It was quite difficult at first, but after sometimes I realized that in order to understand American’s, I had to assimilate into their culture. However I did have some challenging times due to our differences.

Levan T: Your greatest accomplishment?

Adriana: I became more independent. I trusted people less. But I was better able to weed out the people who would be my greatest friends from everybody else. It was from moments like those that I now have this amazing, strong, solid community that my husband, son and I have now.

Levan T: Did you believe that you would succeed in this country?Adriana: yes. I believed that American dream was real and easy.

Levan T: Did you feel any discrimination from people because of your legal status?

Adriana: yes. In the work environment and even in social scene.

Levan T: Do you think every immigrant who came to US find what they looking for?

Adriana: Not every immigrant will find what they looking for. Loneliness and disappointment take over excitement and high expectations.

Levan T: When moving to California does everyone become rich and successful?

Adriana: California continues to receive immigrants from all over the word in search of the dream to pursue wealth and happiness. Nothing will happen easily and to achieve success an immigrant need to apply hard work and discipline. The myth hides the reality of what California has to offer , which comes from the supple plea rues offered by nature, the progressive community than protects the state and set examples to the rest of the country, always looking for better and healthier ways to enjoy life. When moving to California, not everyone will become rich and succeed, but for sure everyone will experience the beauty and uniqueness of the state.

Levan T: do you consider yourself as a successful immigrant?

Adriana: I think I am. I created a community and family that I really care about and that are closer to me than my own family at this point. After years of challenges and obstacles due to my illegal status, I finally got to work on my education and be a mom, wife and productive member of the society. I would say that if I never got to legalize my situation in America, I would always feel an lack of purpose or accomplishment as my core goals , i.e.: education , family , career were out of site for me due to my status . I have to admit that moving to America and live here for 8 years without legality was one of the hardest thing I have done in my life. Been here alone and without rights, had me living on survivor mode for a while, which was really exhausting and lonely.

Levan T: what advice would you give to another person whose trying to immigrate here?

Adriana: If there anything I could tell another young individual that wish to adventure to America as I did. I would say, learn the language as fast as possible, be open mind to understand and act respectfully to the country’s costumes.